Elsewhere in the world, the plight of the LGBTQIA+ community for equality mirrors the quantity and quality of representation it can produce in mainstream cinema, television, and other popular platforms of entertainment.

Compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors, more significant milestones have been accomplished by the LGBTQIA+ community in the Philippines, in its campaign to achieve normalcy and public acceptance. Interestingly, acceptance of homosexuality and gender-bending cultures were widely observed during the pre-colonial era, hence the presence then of male babaylans.

During the Spanish colonial period, babaylans slowly perished, following moral persecutions from the Catholic faith, to which most of the natives subscribed. Discussions on homosexuality remained rare toward the end of Spanish rule. With the introduction of the modernized mass media by the Americans, oppressive consciousness towards homosexuality, dramatically evolved.

As movies and television serials deliberately conceived a specific psychosexual image that practically paints homosexuality as a curse or sickness, Filipino audiences also adopted a new behavior that largely discriminates those belonging to the third sex. Suddenly, there was a cognizant restraint to remain in the closet. As closeted gay men became practically hidden in mainstream cinema, so did real-life closeted queers who were forced to conform to the largely masculine archetype that society dictated.

That said, the same Western perception about and depiction of homosexuality in mass media, also produced a seeming liberationist portal that allowed discursive discussions about the largely oppressive notion against homosexuality, to thrive. During the 1960s, the Philippine gay culture we still know today started gathering form. It was during this neocolonial era when gay literature began to portray homosexuality in a more liberal light. This era also saw the rise of gay activists, prompting a new age where members of the LGBTQIA+ community finally actively participated in movements that do not only advocate for gay rights and equality but also various sociopolitical concerns that were encompassing across all demographic levels and societal sectors.

This smoldering revolution, unfortunately, came to a halt, when Martial Law was implemented in the 1970s. Like many various sectors of society, gay rights advocates were also silenced. The community had it share of being tortured and harassed, under Marcos’ authoritarian regime. During the years of the Martial Law, members of the community sought refuge in the United States, where a growing tolerance was starting to accommodate members of the third sex.

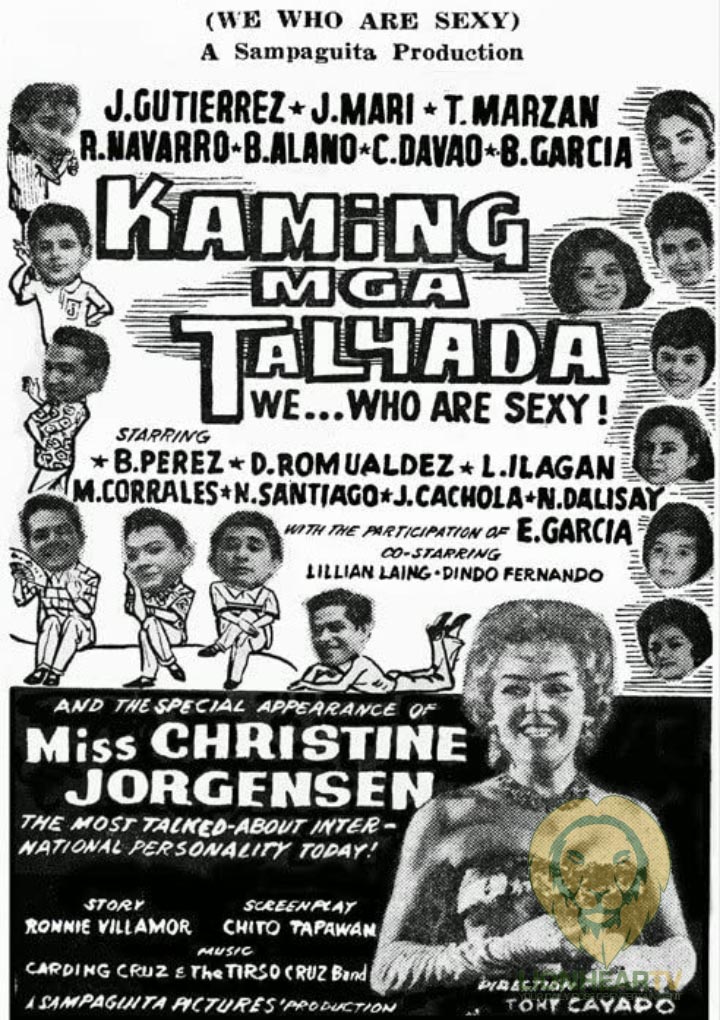

While the fear of persecution became the biggest discouragement for filmmakers during the Martial Law, gay-themed cinema never really dissipated into nothingness, nonetheless. While the film Kaming mga Talyada (1962) is best known as the very first Filipino film to feature a homosexual character, films during the latter years of the Martial Law are remembered for their more profound dissection of homosexuality and various topics attached to it. Works of local cinema legends Ishmael Bernal and Lino Brocka keep their stirring power to spark consciousness and discussions about delicate themes of sociopolitical relevance.

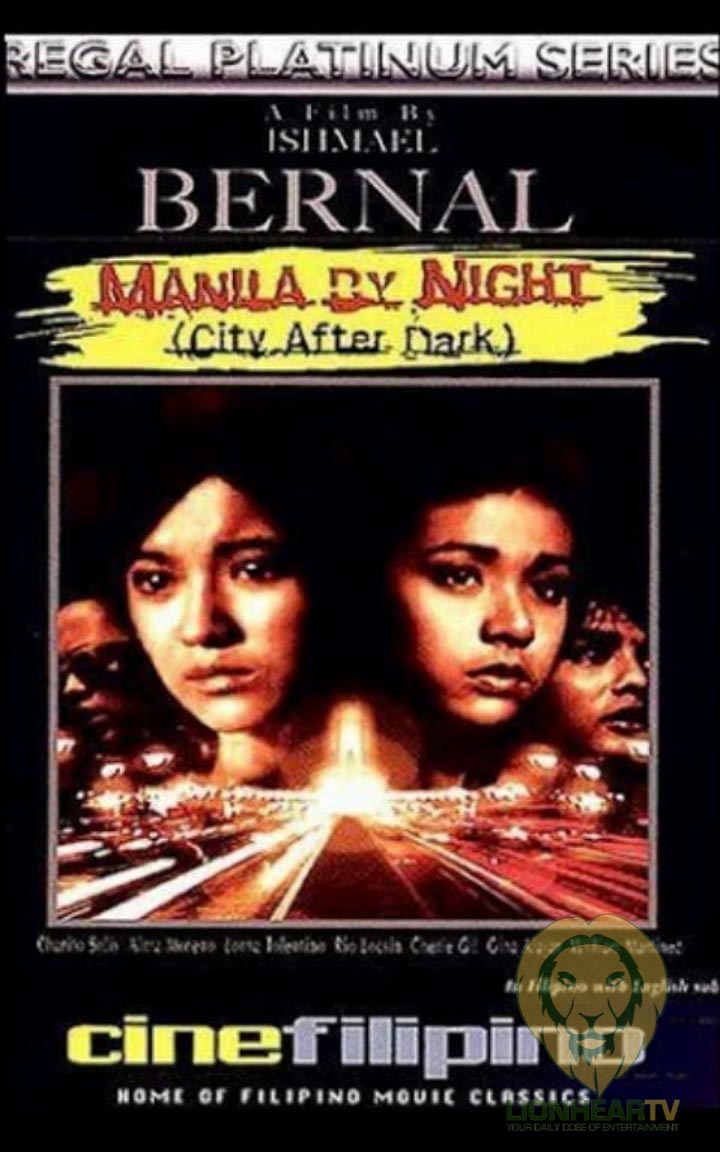

Lino Brocka’s Tubog sa Ginto (1971) and Ang Nanay Kong Tatay (1978), featured powerful gay characters as leads. Similarly, Ishmael Bernal has Salawahan (1979) and Manila By Night (1980) as his timeless masterpieces, both of which showcasing gay characters. That said, gay characters during this era, were mostly limited to effeminate roles.

The appearance of gay characters and themes in cinema ensued in the late 80s and 90s. This era saw intensified efforts to raise pro-LGBT awareness. Literary works such as Ladlad (1993), a collection of gay writings, and Margarita Holmes’s A Different Love: Being Gay in the Philippines (1994), also prospered. Both gay and lesbian groups started gaining ground during this decade, marked by their increasing participation in large demonstrations that advocated for equality and LGBTQIA+ rights. The decade saw the formation of gay groups’ influence—both civic and academic—including Lesbian Collective, ProGay Philippines, and UP Babaylan.

In 1998, the Akbayan Citizens’ Action Party, became the first-ever political party to address LGBT issues.

Through consultation with the community, the Lesbian and Gay Legislative Advocacy Network (LAGABLAB) got formed.

The said lobby group was instrumental in pushing the revision and creation of new bills intended to uphold LGBT rights. It also helps to criminalize discrimination against members of the community. It was in 2003, however, that Ang Ladlad, the first political party to represent the LGBTQIA+ sector, was created.

In cinema, discrete straight-acting queers started to become a common feature in Philippine cinema, during the explosion of indie films in the early 2000s. Auraeus Solito, Joel Lamangan, and Brillante Mendoza were among the Filipino directors to galvanize the breakthrough of the new queer cinema. Auraeus Solito films like Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros (2005), BoY (2009), are both coming-of-age films that integrated its central LGBT themes to sociopolitical motifs, that both regular indie features take into spotlight.

Brillante Mendoza’s films often delved deeper imto themes of poverty, criminality, and social injustice, but some of his works featured powerful homosexual characters, too. Among his more prominent films include Masahista (2005) and Serbis (2Q008); both films starred the now film and TV superstar, Coco Martin.

Television has more concerns when it comes to delivering content that features homosexual themes and characters. As linear viewing would allow anyone from every demographic to access mature content, homosexuality is presented with caution. Same-sex relationships, much less suggestions and actual depictions of same sex-couples doing nature and intimate activities, are discouraged. That being said, depiction of homosexuality and LGBQIA+ characters on national television has drastically changed in the past decade.

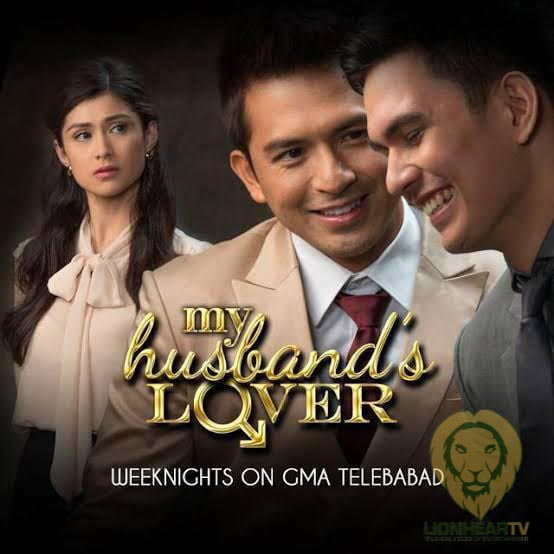

The previous decade saw the emergence of primetime soap operas that didn’t only feature gay characters but also had them in lead roles. My Husband’s Lover (2013) by GMA Network, featured a discreet gay man cheating on his wife over another man.

ABS-CBN drama anthology, Maalala Mo Kaya (MMK), also featured homosexual characters and successfully integrated LGBT themes with socio-relevant issues like poverty and infidelity.

GMA Network’s Out (2004) was a revolutionary magazine show that put the lives of LGBTQIA+ people under the spotlight. It was a groundbreaking event that could have spearheaded subsequent campaigns, until its immediate cancellation. Similarly, ABS-CBN’s primetime series, Till I Met You (2016), was supposed to feature a young man’s struggle to confront his long-harbored feelings for his male bestfriend until the narrative was nearly completely changed to avoid the wrath of fans who were largely expecting the main hetero-couple to have their happy ending. That meant pushing the discreet gay character to the sidelines and also abandoning the possibility of a same-sex romance.

With the explosion of the [still] currently occurring boys’ love phenomenon, a new platform to discuss and raise LGBTQI+ issues is created. Interestingly, it sort of invited mainstream cinema to hop on the bandwagon, hence the release of recent films, Hello Stranger, the Movie, Gameboys: The Movie, and Boyette: Not A Girl Yet, during the pandemic.

The possibility of seeing mainstream television finally tackling these issues and portraying vivid gay characters remains dim—at least, as of the moment. But as the Filipino’s mode of content consumption begins to evolve, so does the availability of queer television and cinema to the mainstream audience. If the trend in more liberal countries is replicated, such a shift in Philippine entertainment should also eclipse pro-gay-rights development in the country.